Ancient cultures seem to have regarded a place as a Sacred Place when it was a

Place where Heaven and Earth could be seen to meet in Harmony at the Horizon. Thus they had an effective luni-solar horizon calendar.

Having seen that, we can understand that prehistoric monuments were not just about alignments but marked optimal observing positions.

These examples demonstrate how they required an overall fit between landscape and sky at every sacred place.

- Vertical scale is x4 to make it easier to see the patterns.

- Orange Solar trajectories split the tropical year into 48 "Tweeks" (7.6 day mean) that are better regarded as quarter-months.

- The year has been split into 16 parts by repeated halving; then each sixteenth part divided into three.

- Solid Blue Lunar lines split cyclical lunistice position variation into 16 periods of about 14 months each.

- Lunistices are the most northerly and southerly moons of the month.

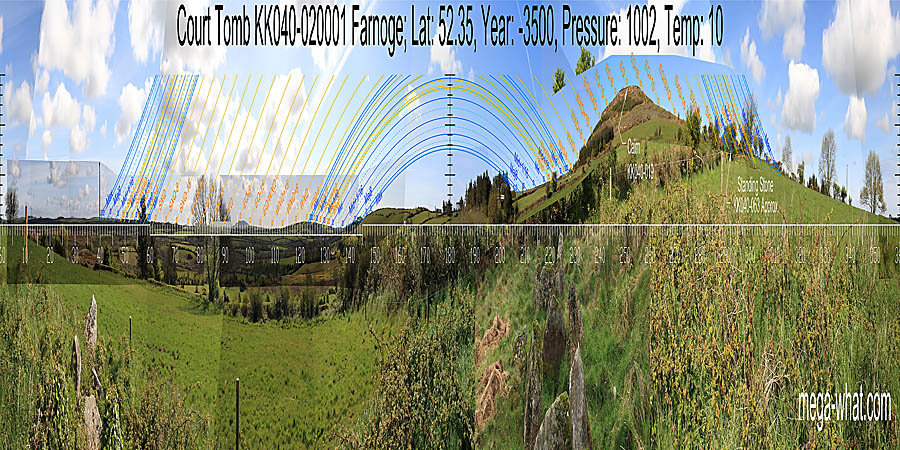

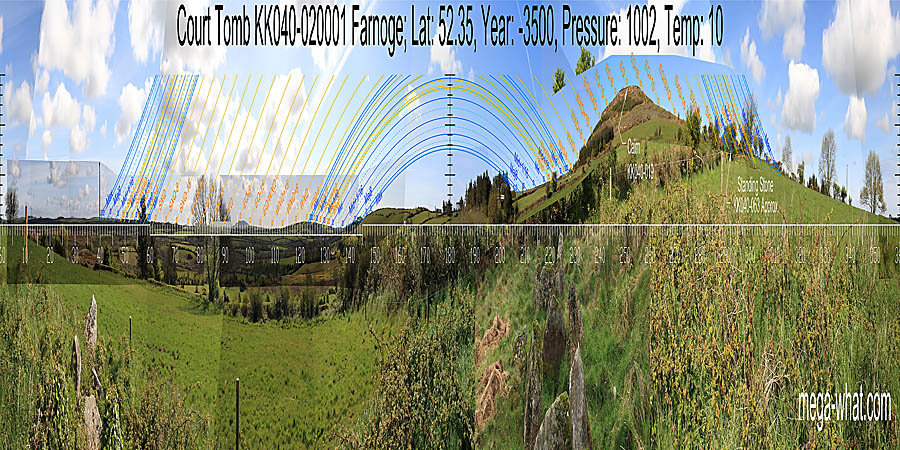

Farnoge Court Tomb

Farnoge Court Tomb c.3500BCE:

This first site shows a clear north-south axis with a dip to one side and a single hill to the other.

South is in a saddle. Westwards, a single hill has the equinox on its top.

The south lunistice zone is on the flat slope leading up to it. The north lunistice zone spans a slight rise on the other slope.

Eastwards, the south lunistice zone spans a dip, ending on a hilltop. The equinox is at the lowest point of the Eastern horizon and the north lunistice zone ends on another hilltop.

North is at the intersect of local and far horizons.

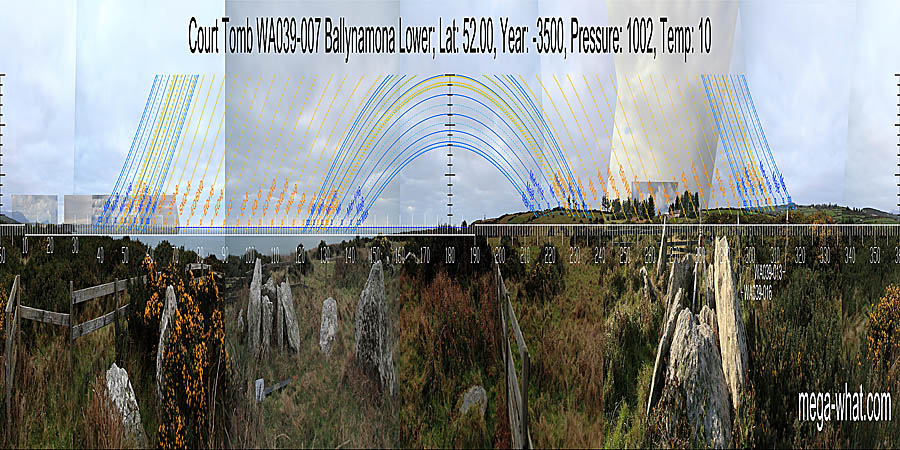

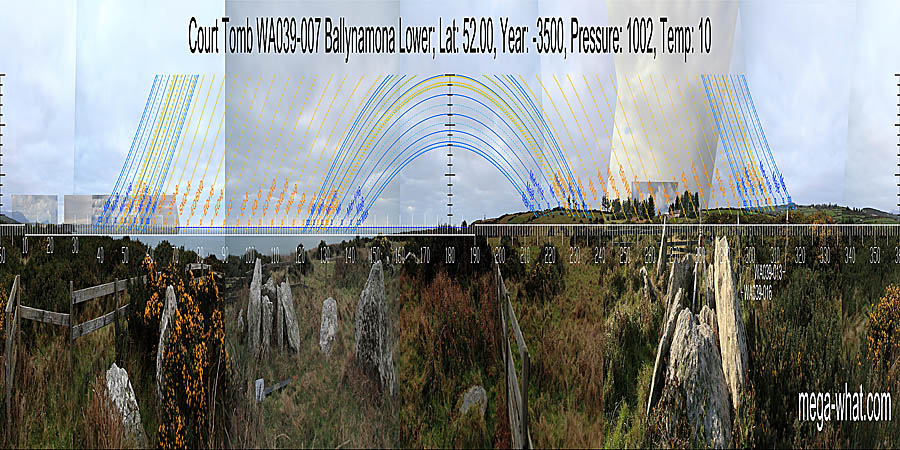

Ballynamona Court Tomb

Ballynamona Court Tomb c.3500BCE:

The second example is a version of single dip to one side of the north-south axis with two hilltops on the other side.

It also shows that sometimes the measuring tool is the landscape profile below the horizon rather than the horizon itself.

South is indicated by the land / sea intersect and the western horizon forms two peaks.

The northern one has major standstill on its top, the southern one is lunar midpoint and the dip between them is a week or so before spring equinox.

Eastwards is a bay and though the sea horizon is flat, the shape of the land forms a dip, with the equinox in the middle.

Across the bay, distant hills mark summer sun rises and the lunistice zone. North is at the intersect.

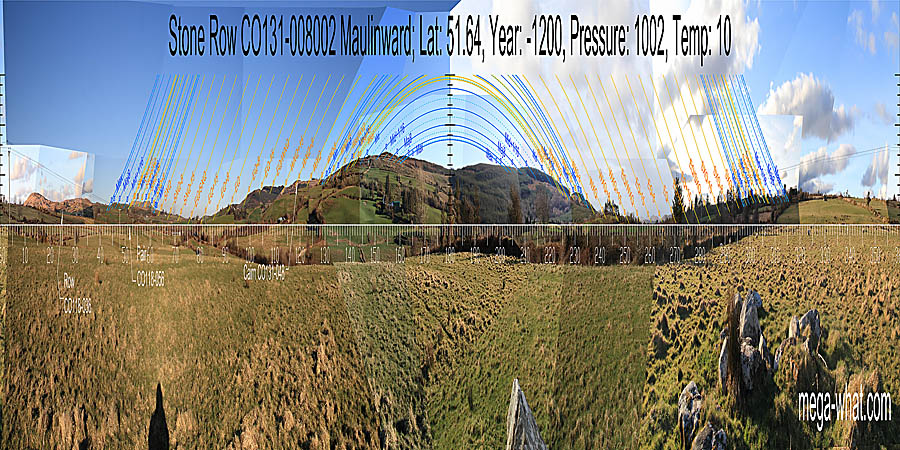

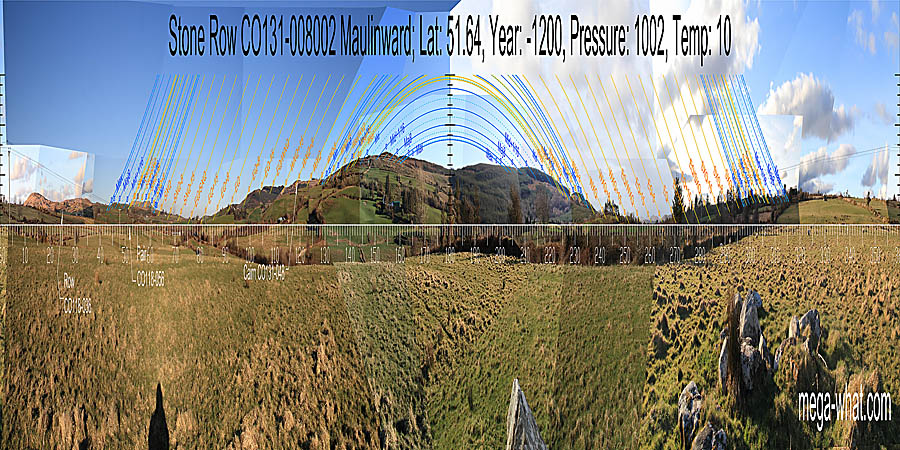

Maulinward Stone Row

Maulinward Stone Row c.1200BCE:

This third one is a rather extreme version of two hilltops to both sides, or single dip to both sides if you prefer.

South is in a saddle. Westwards, the south lunistice zone spans a hilltop and runs down the ridge.

The north lunistice zone runs up a slope and ends at a hilltop. Between these is a dip that bottoms at the Equinox / Winter Cross-Quarter midpoint.

Eastwards, the south lunistice zone spans a hilltop and ends at the basal step. The north lunistice zone spans a distinct block of high ground.

Between them is a dip that bottoms at the Equinox / Summer Cross-Quarter midpoint. North is roughly indicated by a dip.

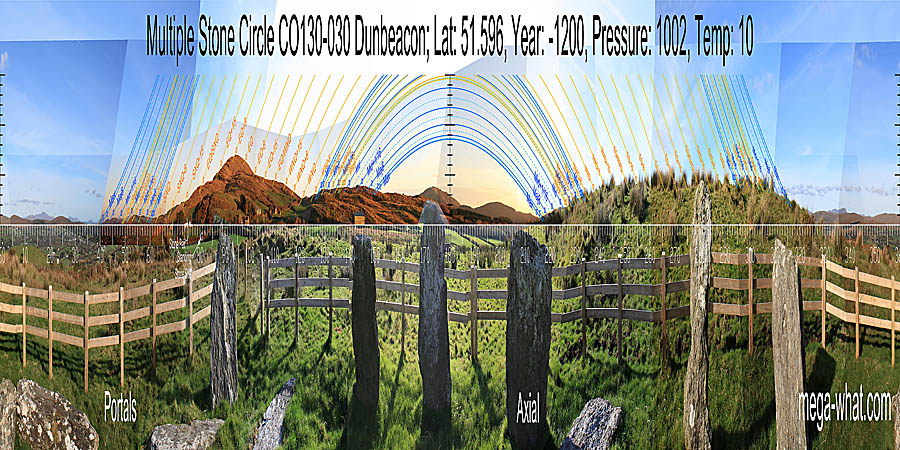

Dunbeacon Stone Circle

Dunbeacon Stone Circle c.1200BCE:

The fourth example is an extreme version of two hilltops to one side, single rise to the other.

It shows how local ground as close as c.20m may be used to form the appropriate overall fit.

North is on a distant hill but the right hand slope of it, as is south. They are rough indicators only, being subservient to the fit of both sides.

The eastern hill has summer cross-quarter at its northern foot and winter cross-quarter at its southern one.

Notice how the equinox has no mark itself but accurate ones a quarter-month before and after it.

The west is very local but fits nonetheless. Accuracy for that sector is provided by an outlier.

© Michael Wilson.